Posted on: 21st October 2016 by Prof. Geoff Scamans

The aluminium can recycling process represents one of the best near-to-closed loop recycling stories in the whole of the worldwide metals industry. However, when you look at the figures, we’re still wasting a huge amount of valuable resources.

I’m passionate about recycling aluminium and, to me, this loss should be avoidable. In this blog I’ll shed some light on what’s happening with can recycling.

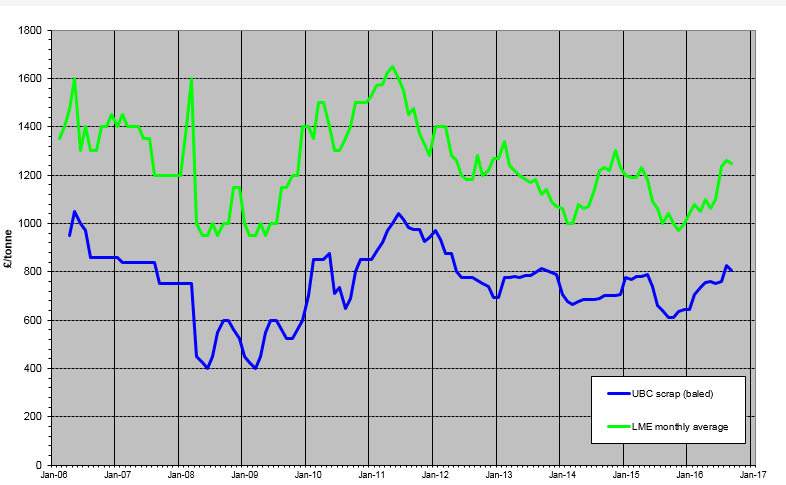

Can scrap price

Since 2006 I’ve kept track of the relative price of primary aluminium on the London Metal Exchange with the price of can scrap. This is the price Novelis pays at their can recycling plant in Latchford, UK.

The graph shows how the price paid for baled cans directly tracks the LME price for primary aluminium. It is always roughly half the primary price, particularly when any premiums are taken into consideration. I don’t know who sets the can scrap price, but it is clearly directly related to the price of prime metal.

The can recycling process

The recycling of can scrap from used beverage cans (UBC’s) is excellent business for aluminium companies like Novelis. This is because they are essentially getting pre-alloyed prime metal back at half price. However, it is not a trivial process to turn this scrap back into the large rolling blocks needed to make the next tranche of cans.

Novelis at Latchford are world leading experts in turning vast numbers of recycled UBC’s back into 27 tonne rolling blocks. Amazingly, each of these blocks contains about 1.5 million recycled cans!

A major part of the can recycling process is to get the alloy composition right to make the can body stock alloy.

The can body and the can end are made from different alloys. Can end alloy is made directly from a prime alloy base. However, both alloys are recycled back into can body stock. Alloying additions and dilutions (using prime aluminium or purer grades of recycled metal from other scrap sources) adjust the composition to that required for can body stock.

Current levels of can recycling

The cans made from recycled UBC’s are indistinguishable to the can-maker from those made from prime aluminium. Can stock must also be made from prime metal to replace the cans that are lost from the recycling loop.

The percentage of recycled UBC’s, and the fraction of these that make it back into can body stock again, varies significantly from country to country.

The UK is close to the world and EU average for UBC recycling at about 65%. Therefore, the recycling loop still loses 35% of all drinks cans, mainly to landfill. This is a huge loss of a valuable resource with a high level of both embodied energy and embodied carbon. Both of these come mainly from the prime aluminium production process.

The second issue is the actual number of recycled cans that find their way back to Novelis at Latchford for making into new cans. This is quite difficult to determine but is around 30 to 40% of all the cans used each year.

Waste of resources

This is clearly a huge waste of a valuable resource, although the UK is not the worst in the world. The US had already lost its trillionth recycled can by 2003. This represents a massive loss of 17.5 million tonnes of aluminium.

Estimates say that the energy required to replace the 50 billion UBC’s wasted in the US each year is equivalent to that lost by pouring away 16 million barrels of oil. In the longer term we could recover some of these lost cans by landfill mining. However, we are a long way from even starting this process today.

The key question is how to raise the awareness of the loss of all these cans from the recycling loop every year. Unfortunately, here’s no appetite for a deposit system in the UK. This system works exceptionally well in the other countries and the US states which use it.

UBC recycling is high in countries where there is a more developed environmental awareness. It is also high where economies are so bad that collecting and recovering discarded cans provides a subsistence level income.

Raising can recycling awareness

The only viable route to solving the UBC recycling problem in the UK has to be through education, particularly in schools. In 2009 there was an opportunity to do this with the BLOODHOUND project. The idea was to make the aluminium alloy wheels of the 1000 mph car from UBC’s collected by the school children signed up to the project. At the same time this would boost the project’s environmental credentials.

The BLOODHOUND team welcomed the proposal. However, after detailed investigation, the wheel alloy was not compatible with the addition of large volumes of UBCs. Furthermore, modifying the alloy composition to allow the incorporation of more UBCs would have raised potential liability issues. These would have been extremely difficult to navigate through.

Eventually the BLOODHOUND wheels were cast in Germany from six tonnes of prime aluminium supplied from Trimet. Sadly, this recycling awareness opportunity was lost.

The BLOODHOUND project has tremendous reach amongst school children in the UK and the wider world. Challenging the children to collect cans would have solved the UBC recycling problem overnight. They would not have let a discarded can reach the ground!

Perhaps it is not too late for the BLOODHOUND project to have an impact on UK and world UBC recycling levels. The energy saved from recycled UBCs could offset the environmental burden of the project. The BLOODHOUND car uses 250kg of rocket fuel in each run. There’s also all the fuel associated with the many air and vehicle miles consumed by the project. The issue now is how to kick-start this concept into life.

Finally, there are some good resources for teachers about the importance of can recycling and how it’s done at www.thinkcans.net